This is really several questions in one. How do birds decide when to migrate? How do they prepare for the journey? How do they know where their destination is? And how do they navigate en route?

Origins of long-distance migration

Long-distance migration patterns have far more complicated origins than short-distance migration, which most likely evolved from a fairly basic need for food. They have developed over countless years and are influenced, at least in part, by the genetic composition of the birds. They also take into account reactions to other elements such as the day’s duration, food sources, geography, and weather.

It seems strange to tropical birds that spend the winter months there to think about moving north and starting a migration. One theory for why these birds make such a difficult journey north in the spring is that their tropical ancestors dispersed from their tropical breeding sites northward over many generations. Compared to their stay-at-home tropical relatives (two to three on average), they were able to raise an average of four to six young due to the seasonal abundance of insect food and longer days. The birds continued to migrate back to their tropical homes during periods of glacial retreat, as the harshness of winter and diminishing food supplies forced them to do so. The majority of North American vireos, flycatchers, tanagers, warblers, orioles, and swallows have evolved from forms that originated in the tropics, which lends credence to this theory.

The mechanisms that trigger migration are diverse and sometimes poorly understood. A combination of shorter days, colder weather, altered food sources, and genetic predispositions can cause migration. Cage bird keepers have observed for centuries that migratory birds experience periods of restlessness every spring and fall, fluttering repeatedly toward one side of their cage. This behavior was named zugunruhe (migratory restlessness) by German behavioral scientists. Diverse bird species, and even subpopulations within a single species, may exhibit distinct migratory behaviors.

The BirdCast project is developing the capacity to forecast when, where, and how far birds will migrate; it’s almost like receiving a weather report.

It’s a treasure for bird watchers and important information for conservation efforts. Knowing the locations and times of birds’ migration allows for the prevention of millions of bird deaths by informing conservation decisions like the positioning of wind turbines and the dimming of building lights on particular nights.

More broadly, accurate migration models enable researchers to study the behavioral aspects of migration, the ways in which migration pathways and timing adapt to changing climatic conditions, and whether there are any relationships between variations in migration timing and ensuing shifts in population size.

How do birds navigate?

During their yearly journey, migrating birds can cover thousands of miles, frequently following the same path with little change from year to year. Often, first-year birds migrate for the first time on their own Despite never having seen it before, they manage to locate their winter residence somehow, and the next spring they return to their birthplace.

Birds use a variety of senses to navigate, so part of the reason why their incredible navigational abilities are still a mystery. Birds can sense the earth’s magnetic field, the sun, and the stars to determine their compass. They also obtain information from landmarks observed during the day and from the location of the setting sun. There’s even proof that smell matters, at least when it comes to pigeon homing.

Certain species migrate annually along certain paths, notably waterfowl and cranes. These routes frequently connect to significant rest stops that offer food supplies that are essential to the birds’ survival. Smaller birds typically migrate across the landscape in broad fronts. Numerous small birds use different routes in the spring and fall to take advantage of seasonal variations in weather and food sources, according to studies using eBird data.

Traveling a distance that could total several thousand miles round trip is a risky and difficult task. The endeavor puts the birds’ physical and mental prowess to the test. The risks of the journey are increased by the physical strain of the journey, inadequate food supplies along the way, inclement weather, and increased exposure to predators.

In recent decades long-distant migrants have been facing a growing threat from communication towers and tall buildings. Many species are attracted to the lights of tall buildings and millions are killed each year in collisions with the structures. The Fatal Light Awareness Program, based in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and BirdCast’s Lights Out project, have more about this problem.

Researchers examine migration using a variety of methods, such as satellite tracking, banding, and a more recent approach using lightweight devices called geolocators. Finding significant wintering and stopover sites is one of the objectives. Once located, these important sites can be saved and protected with the right measures.

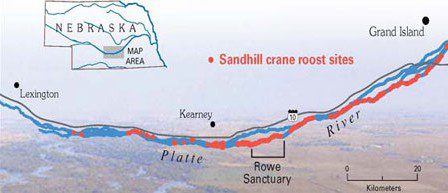

The Central Platte River Valley in Nebraska serves as a staging area for 500,000 Sandhill Cranes and a few endangered Whooping Cranes each spring as they migrate north to breeding and nesting grounds in Canada, Alaska, and the Siberian Arctic.

What is a migrant trap?

Certain locations appear to possess a talent for drawing migrant birds in greater quantities than usual. These “migrant traps” often become well known as birding hotspots. Usually, the local topography, an abundance of food, or the weather are to blame for this.

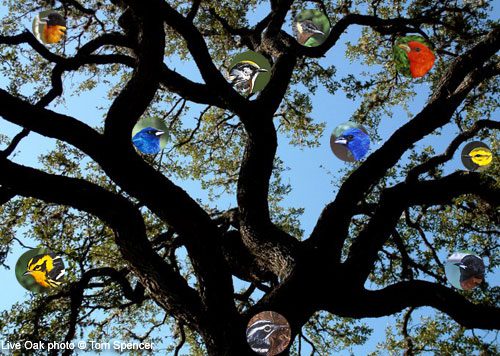

For instance, tiny songbirds that are migrating north in the spring cross the Gulf of Mexico straight and land on the states that border it. When headwinds are brought on by storms or cold fronts, these birds may be almost exhausted by the time they reach land. When this occurs, they flee to the closest area that provides food and shelter, which is usually live oak groves on barrier islands, where a large number of migrants can congregate in what is referred to as a “fallout.” Birdwatchers have taken a great interest in these migration traps, and they have even gained international recognition.

Additionally, as migratory birds follow the land and then pause before launching over water, peninsulas can concentrate them. This explains why areas with a strong reputation as migration hotspots include Point Pelee, Ontario; the Florida Keys; Point Reyes, California; and Cape May, New Jersey.

For those who feed birds in their backyard, spring migration is a particularly good time to attract species they would not typically see. Migrating songbirds may find a backyard appealing if it provides water, a range of food sources, and natural food sources integrated into the landscaping.

FAQ

What do birds do while migrating?

Where do migratory birds go?

Where do birds go in the winter in USA?

How do birds find their way back home after migration?