Worming birds – both aviary birds and companion pets – is a subject that is hotly discussed in avicultural and pet circles, with almost as many opinions as there are bird keepers. Thoughts seem to range between worming your bird every 6 weeks to never doing it at all. And in certain circumstances, both of those protocols can be correct, but lots of factors need to be considered to determine the right protocol for your bird. So, you should consult with an avian vet to determine the best worming protocol for your bird’s individual circumstances.

Getting worming right can avoid bird suffering and a lot of heartbreak when a loved companion or a valuable breeder is lost to something as simple as worms. You can also save a lot of money by not wasting money on worm medications that are not needed.

What has the climate got to do with worming your birds? Simply put, worms (and other intestinal parasites) are spread from bird to bird though the birds’ droppings. Eggs and oocysts (the egg of the coccidia parasite) are shed into the gut and then passed out of the bird. Safely wrapped in the faecal material, these eggs can survive for days to weeks on the floor of the aviary until eaten by a bird or an insect (which is then, in turn, eaten by a bird).

It stands to reason, then, that these eggs will survive longer in a warm, humid environment than a hot (or cold) and dry environment. Birds living in tropical climates are more likely to have intestinal parasites than birds in arid or freezing climates – and will therefore need more frequent worming.

Aviaries can be either full-flight (extending down to the ground) or suspended (a wire floor above the ground). The floor of a full-flight aviary can be bare dirt, grass, sand, gravel, pavers, or concrete – or a mixture of these.

Aviaries can be fully-roofed (completely covered with a solid roof), open-roofed (wire-only roof) or partially roofed (partly fully-roofed).

Suspended aviaries minimise the contact between the birds and their droppings, and can virtually eliminate parasites as a problem in a collection. However, they can be difficult to clean (you can’t climb into them) and may prevent birds from indulging in normal behaviours needed for their mental wellbeing (such as foraging for food or dustbathing). These disadvantages don’t mean that suspended aviaries are bad – when canopy dwellers (such as Eclectus) are housed in them, and environmental enrichment and foraging opportunities are provided, suspended aviaries can be a sound husbandry tool. Worming may only be required once or twice a year, if at all.

On the other end of the spectrum are dirt floored, full-flight aviaries housing ground feeding parrots such as many Australian parrots. Add in a little bit of summer rain and heat, and you have the ‘perfect storm’ that can lead to heavy losses due to intestinal parasites. Birds in this scenario may require worming every six weeks.

Other flooring will have advantages and disadvantages. Grass floors, usually with other plants in the aviary, look great but will attract insects (which can transmit some parasites when they are eaten by the birds). Sand floors can harbour worm eggs but have the advantage of been easily turned over with a rake, reducing direct contact between the birds and parasite eggs.

Concrete floors offer the advantage of been easily cleaned, and birds housed this way may only need worming two or three times each year. Pavers are a near substitute, but the joins between pavers can offer refuge to insects and provide a suitable environment for worm eggs to survive.

Fully-roofed aviaries have two major advantages – they help to keep the aviary floor dry, and they prevent wild birds defecating into the aviary. Partially-roofed or open-roofed aviaries lack these advantages, but they have the advantage of allowing the bird to bathe in the rain and bask in the sun. Again it may come down to a compromise between physical health and psychological wellbeing.

Bird Parasites Treatment and Prevention

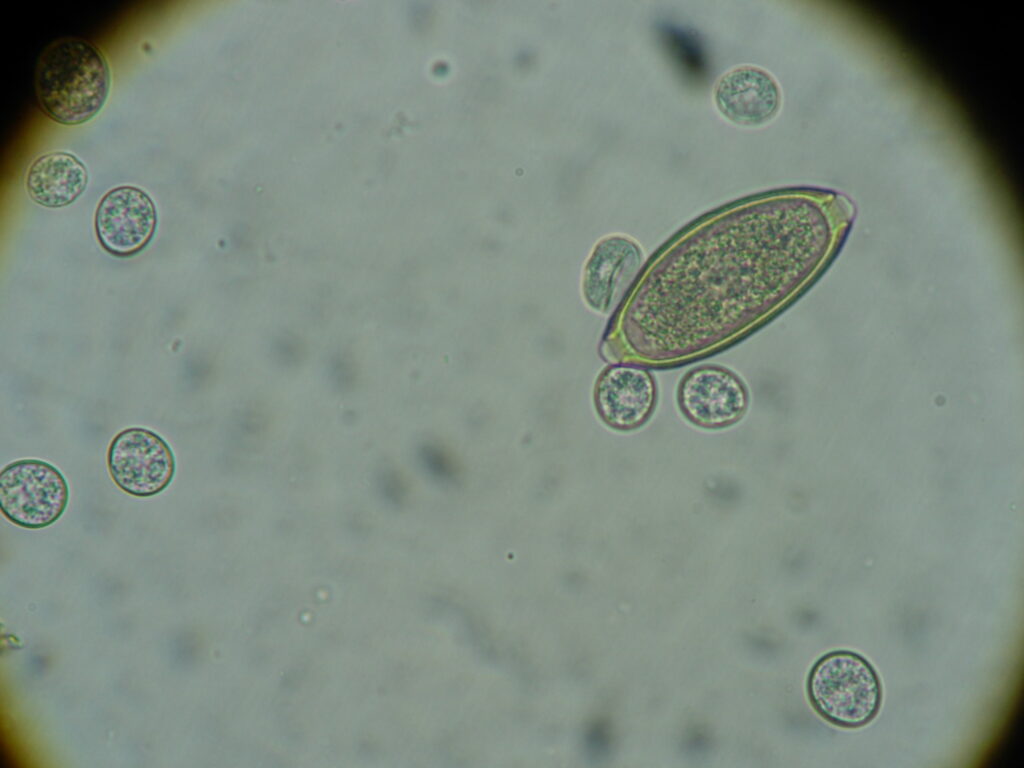

Common worm parasites in pet birds include roundworms (e. g. Ascarids and Heterakis), Capillaria, strongyles, tapeworms and spiruroids (gizzard worms). Birds can become infected by consuming infected beetles or insects. Tape worms and spiruroids have an indirect life cycle, with a variety of beetles and insects serving as intermediate hosts. Usually having a direct life cycle, roundworms infect birds through the consumption of worm eggs carried by an infected bird’s droppings. Earthworms may carry capillaria eggs, but they are not necessary for the capillaria’s life cycle to occur. e. When birds consume worm eggs from other birds’ droppings, they become infected. Worm eggs carried by strongyles in their droppings develop into larvae that climb onto plant material and are consumed by other infected birds.

Symptoms of Worm Infestation

Depending on the kind of worm and the species of bird afflicted, the birds may exhibit poor health, vomiting, diarrhea, malabsorption, or blood in their droppings. When a bird has a large worm burden, its abdomen may swell, but it will usually be emaciated. In severe cases, the muscle mass around the keel bone may be significantly reduced, a condition known as “hatchet breast.” Birds with high worm burdens may die from intestinal blockage or rupture, particularly young birds with low immunity.

The three main species areA. galli, which affects poultry, pigeons and parrots, A. columbae that affects pigeons and parrots and A. platyceri, which is restricted to parrots. The thick-shelled eggs of roundworms can withstand the elements for several months. Infection occurs via ingestion of worm eggs containing larvae. The larvae burrow into the intestinal lining after being digested free of their eggs, which can cause discomfort and diarrhea. After a bird consumes round worm eggs, it takes about three weeks for it to finish its life cycle. Once it does, the adults mature and become ready to lay eggs, which the bird excretes.

Young birds that have just flown and are feeding on the ground where adult birds have left droppings containing worm eggs are the birds most at risk of developing serious diseases. While young birds often have weaker immune systems and are more susceptible to infections with large populations of worms that can result in intestinal blockage, a potentially fatal illness complication, adult birds typically have some immunity to control the number of worms in their bodies.

A particular kind of roundworm known as heteroakis inhabits the caeca, which is the avian equivalent of the human appendix, in chickens, pheasants, peacocks, and other gallinaceous birds. Heterakis worm species generally don’t spread disease on their own, but they can harbor the amoeba-like organism Histomonas meeagridis, which is the cause of “Black Head.”

Often referred to as “Hair-worms,” these tiny, slender worms eat their way deeply into the lining of the oesophagus and small intestine, resulting in ulcers. Numerous species affect various bird species, and they are all major causes of disease. Similar to roundworms, capillaria worms have a direct life cycle, and eating soil or other items tainted with bird droppings can harm birds. Earthworms can act as carriers.

These are segmented, flat worms that usually pass their eggs by releasing segments from their tail end called “proglottids,” which contain eggs. These segments are visible to the unaided eye, but they are only occasionally passed, so unless a proglottid has ruptured, it may be challenging to identify tapeworm eggs in bird droppings under a microscope. A variety of insects and other invertebrates act as intermediate hosts in the indirect life cycle. A wide range of distinct yet related tapeworm species with various intermediate hosts can be found in various bird species, such as parrots, cockatoos, finches, and chickens.

Most of the time, tapeworms are not very harmful and only result in mild illness or loose droppings. The exception is when it comes to insectivorous finches, like parrot finches, where intestinal blockage and death due to tapeworms are common.

Pet birds or aviary birds?

Many breeders and pet stores advise having a pet bird wormed every three months for the rest of its life if it is kept indoors alone. This guidance is based on the suggested worming schedules for cats and dogs. Worming a pet bird is a good idea as soon as it is purchased, but in a home with just one bird, it is highly unlikely that the bird will come into contact with parasite eggs—at least not to the point where it needs to be wormed every three months!

Conversely, avian birds are much more likely to become infected with parasites and will need to be wormed on a regular (and occasionally frequent) basis.

FAQ

How do you deworm birds naturally?

How do you treat worms in birds?

How do you know if a bird has worms?

What causes birds to get worms?