Bird migration is one of the most fascinating and inspiring natural phenomenabut how do scientists figure out where all those birds are going?

From the earliest origins of bird banding to high-tech approaches involving genomic analysis and miniaturized transmitters, the history of bird migration research is almost as captivating as the journeys of the birds themselves. My book Flight Paths, forthcoming in 2023, will take a deep dive into the science behind these techniques and the stories of the people who developed them, but in the meantime, below you can read a selection of milestones that trace our unfolding understanding of migration.

Indigenous cultures develop a range of legends and stories about migratory birds. Athabascan peoples in Alaska, for example, tell the story of Raven and Goose-wife, in which Raven falls in love with a beautiful goose but cannot stay with her because he cant keep up when the family of geese migrates south over the ocean.

While Aristotle correctly recognized some aspects of bird migration in his Historia Animalium in the 4th century, BC, he hypothesizes that swallows hibernate in crevices and that some winter and summer residents are actually the same birds in different plumages.

Inspired by Aristotle, Swedish priest Olaus Magnus suggests that swallows hibernate in the mud at the bottom of lakes and streams. This misconception will persist into the 1800s.

English minister and educator Charles Morton theorizes that birds migrate to the moon for the winter. Although this sounds ridiculous today, he correctly conjectured that birds may be spurred to move to new areas by changing weather and a lack of food and even noted that body fat might help sustain them on their journey.

John James Audubon ties silver thread to the legs of Eastern Phoebe nestlings and identifies them when they return to the same area the following springor, at least, so will later claim. Biologist and historian Matthew Halley cast doubt on this in 2018 when he noted that Audubon was actually in France in spring 1805 when the phoebes would have returned.

German villagers shoot down a White Stork that had a spear made of African wood impaled in its side. Dubbed the pfeilstorch (or arrow stork), this unfortunate bird provides some of the first concrete evidence of migration between continents.

Ornithologist William Earl Dodge Scott is touring the Princeton University astronomy department when hes offered a view of the full moon through a telescope. Astonished to see migrating birds silhouetted against the face of the moon, he is able to use his observations to calculate a rough estimate of how high they must be flying.

Climbing a hill outside Madison, Wisconsin, historian and amateur ornithologist Orin Libby counts 3,800 calls by migrating birds over the course of five hours on one September night. Many of the calls seemed almost human, he will later write, and it was not difficult to imagine that they expressed a whole range of emotions from anxiety and fear up to good-fellowship and joy. These calls will eventually be dubbed nocturnal flight calls” and be used as one way of monitoring bird migration.

Hans Christian Cornelius Mortensen places metal rings around the legs of starlings in Denmark to study their movements, the beginning of the scientific use of bird banding.

At a meeting in New York City, members of the American Ornithologists Union vote to form the American Bird Banding Association, the direct forerunner of todays USGS Bird Banding Laboratory. Its mission is to oversee and coordinate bird-banding efforts at a national scale.

The U.S. Bureau of Biological Survey assumes authority over the bird banding program after the Migratory Bird Treaty Act passes in 1918. The agencys Frederick Charles Lincoln will use banding records from waterfowl to develop the concept of migratory flywaysfour major North America flight routes around which bird conservation is still organized today.

David Lack and George Varley, biologists working for the British government, use a telescope to visually confirm that a mysterious military radar signal is being generated by a flock of gannets. Its the first concrete proof that radar can detect flying birds, but the idea is not immediately embraced: At one meeting, Lack later writes, after the physicists had again gravely explained that clouds of ions must be responsible, Varley with equal gravity accepted their view, provided that the ions were wrapped in feathers.

Louisiana State University ornithologist George Lowerys moon-watching observations in the Yucatan, using techniques inspired by Scotts original full moon observations in 1880, provide evidence that some birds do indeed migrate across the Gulf of Mexico instead of taking a land route over Mexico.

Oliver Austin, an ornithologist leading wildlife management in Japan under the Allied occupation that followed World War II, describes the traditional Japanese method of catching birds for food using silk nets strung between bamboo poles. Mist nets will soon become the primary method for capturing songbirds for ornithological research.

George Lowery and his collaborator Bob Newman oversee a massive effort to recruit volunteers across the continent to record moon-watching observations during fall migration. Telescopes swung into operation at more than 300 localities as people by the thousands took up the new form of bird study, writes Newman. By the end of the season, reports had been received from every state in the United States and all but one of the provinces of Canada. Due to the difficulties in analyzing such large amounts of data without computers, Lowery and Newman will not publish the full results until 1966. Their work provides the first continent-wide snapshot of migration patterns.

Illinois Natural History Survey ornithologist Richard Graber and engineer Bill Cochran record nocturnal flight calls for first time, rigging up a tape recorder with bicycle axles to hold the six thousand feet of tape needed to record a full night of migration.

Richard Graber tags a migrating Gray-cheeked Thrush in Illinois with a miniature radio transmitter developed by Bill Cochran. That night, he follows it for 400 miles in an airplane as it continues its migratory journey. Each of us, at times, must stand in awe of mankind, of what we have become, what we can do, Graber will write in Audubon. The space flights, the close-up lunar photographs, the walks in spaceall somehow stagger our imagination. I was thinking about this as I flew south from Northern Wisconsin [the next morning], having just witnessed an achievement of another kind by another species.

Ornithologist Sidney Gauthreaux, who studied for his PhD under George Lowery, publishes Weather radar quantification of bird migration, the first systematic study of bird migration patterns using the relatively new technology of weather radar.

Bill Cochran tracks a radio-tagged Swainsons Thrush for 930 miles on its migration, following it from Illinois to Manitoba over the course of a week in a modified station wagon with a radio receiver sticking out of the top.

Johns Hopkins Universitys Applied Physics Lab carries out the first field tests of satellite transmitters on birds using the Argos satellite systemlaunched in 1978 for the purpose of tracking oceanic and atmospheric data. Swans and eagles are early subjects.

British seabird biologist Rory Wilson tracks the movements of foraging penguins using a device of his own invention that he calls a Global Location Sensor. It uses ancient navigation principles to calculate and record a birds location using only a tiny light sensor and clock. These devices will later be better known as light-level geolocators.

Canadian scientist Keith Hobson and his colleagues publish a paper demonstrating that its possible to determine where a migrating songbird originated by analyzing the amount of deuteriuma rare isotope of hydrogen that occurs in varying amounts across the landscapein its feathers.

Selective availability, a U.S. government practice which intentionally limits the accuracy of GPS technology available for non-military use, is switched off. Ornithologists quickly begin creating GPS devices for tracking the movements of birds.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology launches eBird, a community science platform that lets birdwatchers upload records of what they observe to a database that is accessible to ornithologists, ecologists, and other researchers. Today more than one billion sightings have been contributed from around the world.

A satellite transmitter implanted in a Bar-tailed Godwit dubbed E7 tracks the birds astonishing nonstop 7,000-mile migration from Alaska to New Zealand over the open water of the Pacific Oceanthe equivalent, according to a USGS press release, of making a roundtrip flight between New York and San Francisco, and then flying back again to San Francisco without ever touching down.

Ornithologists Kristen Ruegg and Tom Smith launch the Bird Genoscape Project, an effort to map genetic diversity across the ranges of 100 migratory species. It will enable ornithologists to identify where in North America a migrating bird came from by analyzing its DNA.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology scientists kick off the second iteration of BirdCast, a project that uses weather radar data to predict nights of especially intense bird migration activity. (The original BirdCast, started in 2000 by Sidney Gauthreaux, was discontinued after a year due to the limits of the technology available at the time.) One major result of the project is initiatives that encourage cities to shut off disruptive nighttime lighting when large numbers of migrating birds are likely to be on the wing.

The Motus Wildlife Tracking System, which uses miniature radio transmitters and an automated network of ground-based receiver towers, is launched in Canada. More than 30,000 animals (mostly birds) will be tracked by the system in the next decade.

Light-level geolocators confirm long-held suspicions that Blackpoll Warblers, songbirds that weigh roughly the same as a ballpoint pen, make a nonstop 1,400-mile, three-day flight over the eastern Atlantic Ocean during their fall migration from New England to South America.

Project Night Flight, the largest nocturnal flight call monitoring project to date, operates more than 50 recording stations in Montanas Bitterroot Valley. Spearheaded by Kate Stone and Debbie Leick, staff members at private research and conservation property MPG Ranch, Project Night Flight will record more than 100,000 hours of data in the next two years.

Icarus, a new space-based wildlife tracking system with receivers on the International Space Station, begins operations. The initiatives overseers aim to provide transmitters that are lighter, lower-cost, and provide better-quality data than any trackers used before.

This piece originally ran in the Spring 2022 issue as A Brief History of Discovery. To receive our print magazine, become a member by making a donation today.

Pledge to stand with Audubon to call on elected officials to listen to science and work towards climate solutions.

Why do birds migrate?

Birds migrate when they move from low-resource or diminishing areas to high-resource or expanding areas. Food and places to build nests are the two main resources that are being sought after. Heres more about how migration evolved.

When springtime arrives in the Northern Hemisphere, nesting birds migrate northward to take advantage of budding plants, increasing insect populations, and an abundance of nesting sites. The birds migrate south once more as winter draws near and there are fewer insects and other food sources. Although escaping the cold is a driving force, many speciesincluding hummingbirdscan tolerate below-freezing temperatures provided there is a sufficient supply of food.

The large-scale, periodic movements of animal populations are referred to as migration. Migration can be viewed by taking the distances traveled into account.

- Permanent residents do not migrate. They are able to find adequate supplies of food year-round.

- When migrating short distances, such as from one mountainside’s higher to lower elevation, they move relatively little.

- Medium-distance migrants cover distances that span a few hundred miles.

- Typically, long-distance migrants travel to wintering grounds in Central and South America from their breeding ranges in the United States and Canada. Approximately 350 species of birds in North America are migratory over great distances, despite the difficult travels involved.

Within each category, the pattern of migration can differ, but it varies most among short- and medium-distance migrants.

Range maps This animated map shows where Common Yellowthroats occur each week of the year. The colors indicate the numbers of birds: darker or more purple colors indicate higher numbers of birds, lighter, yellow colors indicate fewer birds. Map from

Using the range maps in your field guide to ascertain whether and when a specific species might be present is always a good idea. Range maps are especially useful when working with migratory species. They can be confusing, though, as bird ranges can change from year to year, especially for invasive species like redpolls. Furthermore, some species’ ranges can change fairly quickly, sometimes even within the time it takes for a field guide to be republished. (The Eurasian Collared-Dove is the best example of this problem. ).

Digital range map versions that are driven by data are starting to address these limitations. The hundreds of millions of eBird observations that birdwatchers from all over the world have submitted have made the maps possible. Scientists can now create animated maps that depict a species’ ebb and flow across a continent over the course of a year thanks to “Big Data” analyses, which also help them understand more general patterns of movement.

Migration is a fascinating study and there is much yet to learn. Songbird Journeys, by the Cornell Labs Miyoko Chu, explores many aspects of migration in an interesting and easy-to-read style. The Cornell Labs Handbook of Bird Biology provides even more information on the amazing phenomenon of bird migration.

How do birds navigate?

During their yearly journey, migrating birds can cover thousands of miles, frequently following the same path with little change from year to year. Often, first-year birds migrate for the first time on their own Despite never having seen it before, they manage to locate their winter residence somehow, and the next spring they return to their birthplace.

Birds use a variety of senses to navigate, so part of the reason why their incredible navigational abilities are still a mystery. Birds can sense the earth’s magnetic field, the sun, and the stars to determine their compass. They also obtain information from landmarks observed during the day and from the location of the setting sun. There’s even proof that smell matters, at least when it comes to pigeon homing.

Certain species migrate annually along certain paths, notably waterfowl and cranes. These routes frequently connect to significant rest stops that offer food supplies that are essential to the birds’ survival. Smaller birds typically migrate across the landscape in broad fronts. Numerous small birds use different routes in the spring and fall to take advantage of seasonal variations in weather and food sources, according to studies using eBird data.

Traveling a distance that could total several thousand miles round trip is a risky and difficult task. The endeavor puts the birds’ physical and mental prowess to the test. The risks of the journey are increased by the physical strain of the journey, inadequate food supplies along the way, inclement weather, and increased exposure to predators.

In recent decades long-distant migrants have been facing a growing threat from communication towers and tall buildings. Many species are attracted to the lights of tall buildings and millions are killed each year in collisions with the structures. The Fatal Light Awareness Program, based in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and BirdCasts Lights Out project, have more about this problem.

Researchers examine migration using a variety of methods, such as satellite tracking, banding, and a more recent approach using lightweight devices called geolocators. Finding significant wintering and stopover sites is one of the objectives. Once located, these important sites can be saved and protected with the right measures.

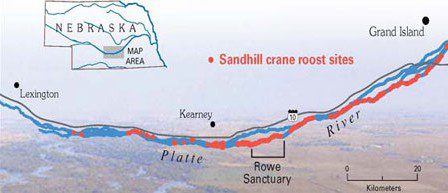

The Central Platte River Valley in Nebraska serves as a staging area for 500,000 Sandhill Cranes and a few endangered Whooping Cranes each spring as they migrate north to breeding and nesting grounds in Canada, Alaska, and the Siberian Arctic.

FAQ

What is the science behind bird migration?

What is the main reason that birds migrate?

What is the ultimate cause of bird migration?

What is one possible explanation for why some birds migrate?